A Heart that Beats in Beyoğlu

From piano to bağlama, accordion to kemençe, cello to kanun, Athens to Crete and Istanbul —Asineth Fotini Kokkala has been exploring her way through the universe of music since childhood. Each step in her journey builds invisible bridges: not only between the two shores of the Aegean but also across distant geographies. We sat down with her to get accross these bridges —of sound, memory, and belonging.

Do you have a childhood memory that hints at the “you” of today?

I’m the third of four children. My parents were pharmacists. The person who first brought music into our lives was my uncle’s wife. We were neighbors in Athens, and I grew up like a sister to their daughters.

When I was about six, my uncle had to move his family to Crete as a doctor. His wife —my Venezuelan aunt— was the one who brought true color into our childhood: music, laughter, joy. I adored my cousins. One of them became the famous pianist Alexia Mouza Arenas, and the other now lives in Copenhagen.

Every summer, we reunited in Crete. Though it wasn’t my ancestral homeland, it became “my village.” My grandmother was still alive then; she divided her time between Athens and Crete. When I was seven, we lost her. My aunt, a pianist, was my first real inspiration. I began with piano as well.

My father, although not a professional musician, loved music. Our house often came alive with friends. We had a ritual —one song before dinner, another after. My earliest memory is of falling asleep to people singing around the table, being carried to another room, crying, and then being brought back into the circle of music. There was a deep comfort in those nights.

How did you first come across the kanun?

By chance. I started piano lessons at six in a small course, which also had a children’s choir singing traditional songs. After primary school, I entered one of Greece’s selective music schools. From the very first day, I felt at home. Children came from every corner of Athens.

The first year, I played piano —and a little bağlama, since we had to learn both a Western and a traditional instrument. We could also pick a third. At first, I chose accordion. But when the teacher left, I had to choose again. We experimented with different instruments, almost playfully. The moment I heard the kanun, I thought, “Now this is something.” That’s when I chose it. Who knows—if I had stayed with the accordion, maybe I’d be in Paris or Argentina today!

Photos: İmge Yüksel

So you learned Western and makam music side by side…

Definitely. I had an extraordinary kanun teacher —the one who first told me about Houdetsi in Crete. That’s where Ross Daiy founded the Labyrinth Musical Workshop, a world-renowned school that brings in musicians —mostly from Anatolia and the Eastern countries, such as Iran, Afghanistan, and India— to give workshops.

There, you work three hours in the morning and three in the afternoon for a whole week. At fifteen, I went with my teacher, and it was transformative. I met Turkish musicians for the first time: kanun master Göksel Baktagir, oud player Yurdal Tokcan. The next year, Halil Karaduman was there. I also joined ney master Ömer Erdoğdular’s classes —he later became my mentor. In the meantime, I had also begun playing cello outside of school.

Can we call you a multi-instrumentalist?

I guess so, though it’s not a label I wear easily. Some musicians dedicate their lives to a single instrument, diving into its deepest layers. I don’t see myself that way. For me, each instrument is just a vessel for what I need to express. I don’t think of myself as “a kanun player” or “a cellist.” Whatever’s inside me, I let it flow through whatever is in my hands.

Photo: Eric Theze

And how did Istanbul find its way into your veins?

Through my teachers in Crete, especially Ömer Erdoğdular —an old-school Ottoman musician steeped in makam, who spoke no English at all. We communicated only through music, and outside class hours, he taught us tirelessly from morning until night.

Each summer, I attended different seminars in Crete. One year it was Erkan Oğur, another year Derya Türkan with the classical kemençe, but every year I returned to Erdoğdular’s classes. I always leaned toward the Turkish seminars. Of course, there were African musicians too —I could have gone toward the kora, but I didn’t.

After high school, I studied folk and traditional music at the University of Epirus, where we also learned makam music. By the end of my third year, I had decided: “I’m going to Istanbul for Erasmus!”

In Greece, many musicians also work with makam through classical instruments. Was your drive to come to Turkey about reaching the source —Anatolia itself?

Back then —twenty years ago— there weren’t so many. My Crete experience had marked me deeply. For a fifteen-year-old, it was overwhelming. Something inside me longed for Istanbul.

My father resisted. He grew up in a village that had been at the heart of rebellion against the Ottomans, so he feared them. He imagined that if I went to Istanbul, Ottomans would greet me at the city gates with swords, I guess!

Eventually, I visited on a tour, fell in love with the city, and couldn’t get it out of my mind. In 2010, I arrived for Erasmus at Yıldız Technical University. I thought it would be temporary. But then came an internship… and I stayed.

I’m glad you stayed… So, if you had to compare Athens and Istanbul?

Athens feels like a village compared to Istanbul. Yet emotionally, I see them as siblings. In both, you can lose yourself in the crowd. You know that phrase about Istanbul: “They call it chaos, we call it home.” People who don’t live here may not love it.

Maybe chaos is nourishment for us.

Exactly… For instance, I compare Kadıköy and İzmir to Thessaloniki. But Beyoğlu and Istanbul are similar to Athens, in terms of feeling. In Beyoğlu, you can see all sorts of unrelated things side by side. In the other cities, there’s the sea and a much more relaxed atmosphere, but in Beyoğlu, I truly feel at home.

And eventually, you married someone from Turkey. Do you think the two cultures complete each other?

Absolutely. I’m not the same Fotini I was before coming here. I carry both cultures now. With my husband, it feels like we’re perfectly aligned, even though he doesn’t speak Greek. We make music together in the İstos Choir. That perfect, effortless vibe when you just click.

Remember, I was talking about Ömer Erdoğdular? He was like a dad to me. A devout Muslim, he exuded a warmth that made me feel incredibly close to him. It was a unique kind of love. Being a foreigner, I also found it easier to move across Turkey’s diverse religious and social circles. I was always exotic, able to build connections with white Turks, Kurds, Roma… from the lively streets of Tarlabaşı, where I once lived, to the polished avenues of Etiler. Fascinatingly, some of these worlds might never have crossed paths —except through me.

Music, of course, opens countless doors. So, what excites you most musically? What are you really chasing?

For me, the Istos Choir became a wonderful opportunity. Istos Publishing said, “Let’s start a music workshop. Let’s do rebetiko.” This was in 2017. Before that, I had been playing in Beyoğlu with Sinafi Trio, a trio of women from Greece, performing in meyhanes and türkü bars almost four nights a week. Back then, as a Greek musician, both the audience and employers had very clear expectations: a bit of Greek music, sirtaki, or the kind of rebetiko soundtrack from Costas Ferris’ film Rembetiko. But I kept saying, “Rebetiko isn’t just that!”

With Sinafi Trio, we worked hard to play the music we wanted. We introduced lesser-known rebetikos, other songs we loved, and even Turkish folk and classical art music pieces. Our repertoire was expansive. In Turkish conservatories, you are either THM —folk— or TSM —classical Turkish music. “Oh, you play the kanun? Then TSM.” But Tamburi Cemil Bey played in both meyhanes and palaces. I wanted to break that barrier. I wanted both. Couldn’t I have both?

So when Istos offered the workshop, I was thrilled. In the first year, I brought three new songs to every lesson. Later, I realized we had gone overboard. Rebetiko itself has two main schools: İzmir and Piraeus, each distinct in style and attitude. Gradually, we expanded into traditional Greek music: why does Epirus sound closer to Albania than Crete? What’s happening in Thrace? You notice similarities with Bulgaria and Turkey. Slowly, we delved into the anthropology of sound —an incredibly rewarding journey to me.

And your thesis? Can we touch on that a bit?

I just want to finish it, more than anything! My focus is on the contribution of the Greek community to Istanbul’s nightlife, particularly from the 1950s to the 1980s. Until the ’50s, it was the golden age of Greek musicians with vibrant musical production. Then came the 1942 Wealth Tax, the 1955 pogroms, the 1964 expulsions, and the Cyprus crisis of 1974 —one after another. The Rum (native-born Greeks of the former Ottoman Empire) population dwindled, and the city lost much of its multicultural character. Yet in the ’80s and ’90s, interest in taverna and Greek music surged again. Rums were no longer the “dangerous others,” but exotic figures. Taste varied socially: middle-class urban Turks resonated with their Rum neighbors’ music, whereas rural migrants less so. My thesis examines how Greek music became popular and reintegrated into Istanbul’s cultural fabric even as the native Greek population declined.

Most Istos Choir members aren’t Rum either; they come from a wide range of identities and professions, and many don’t even speak Greek.

Exactly. We only have one Rum member. Istos isn’t about chasing “authentic Greek music.” In my music, identities intermingle. Who is Turkish, who is Greek —these lines blur. We mix Anatolian influences with a touch of alaturka and makam music. This style doesn’t always appeal to a secular, Orthodox Greek —but it resonates in its own way.

Mondays —what do they mean to you?

No concerts on Mondays. So it’s my most stable day. For nine years, Istos’ rehearsals have been every Monday. After the pandemic, we also started NikoTeini videos on Mondays —just two musicians, Niko and Fotini, on a couch, playing without the pressure of perfection. Over two years, this routine shaped our own sound. NikoTeini became, well, addictive —like nicotine.

Ha ha! That’s brilliant. I heard you even performed abroad as NikoTeini. How was the audience?

Australia was our latest adventure. I feel very lucky to do this. There’s a sizable Greek diaspora in Melbourne, Adelaide, and Sydney, and they attended our concerts. But in Tasmania, almost no Greeks —there, the audience was completely attentive to the music itself, pure and unfiltered. That’s something rare for me.

Like aliens had come to listen?

Exactly!

Which Greek islands do you love besides Crete? There are hundreds, of course…

Lesvos. It’s the people who make a place special. We have wonderful musician friends there: Nikos Andrikos and Maria Seitanidou. It’s an island that carries both cultures, and every year we go there with the Istos Choir for a workshop. I’m not sure if they’d even accept this, but I often compare Crete and Lesvos —they feel very similar. Just like I used to compare my father to Turks! Anything else? I really love the energy of Amorgos. But it’s been a long time since I visited a new island.

Photo: Dilek Çilingir

What’s next on the horizon? You have two concerts in Istanbul with Ara Dinkjian, on September 28 and October 1, which sold out the moment tickets went on sale. Perhaps there are other exciting plans I don’t even know about…

Could anything be more thrilling than collaborating with Ara Dinkjian? I still can’t believe it!

How did this musical kinship with Ara start?

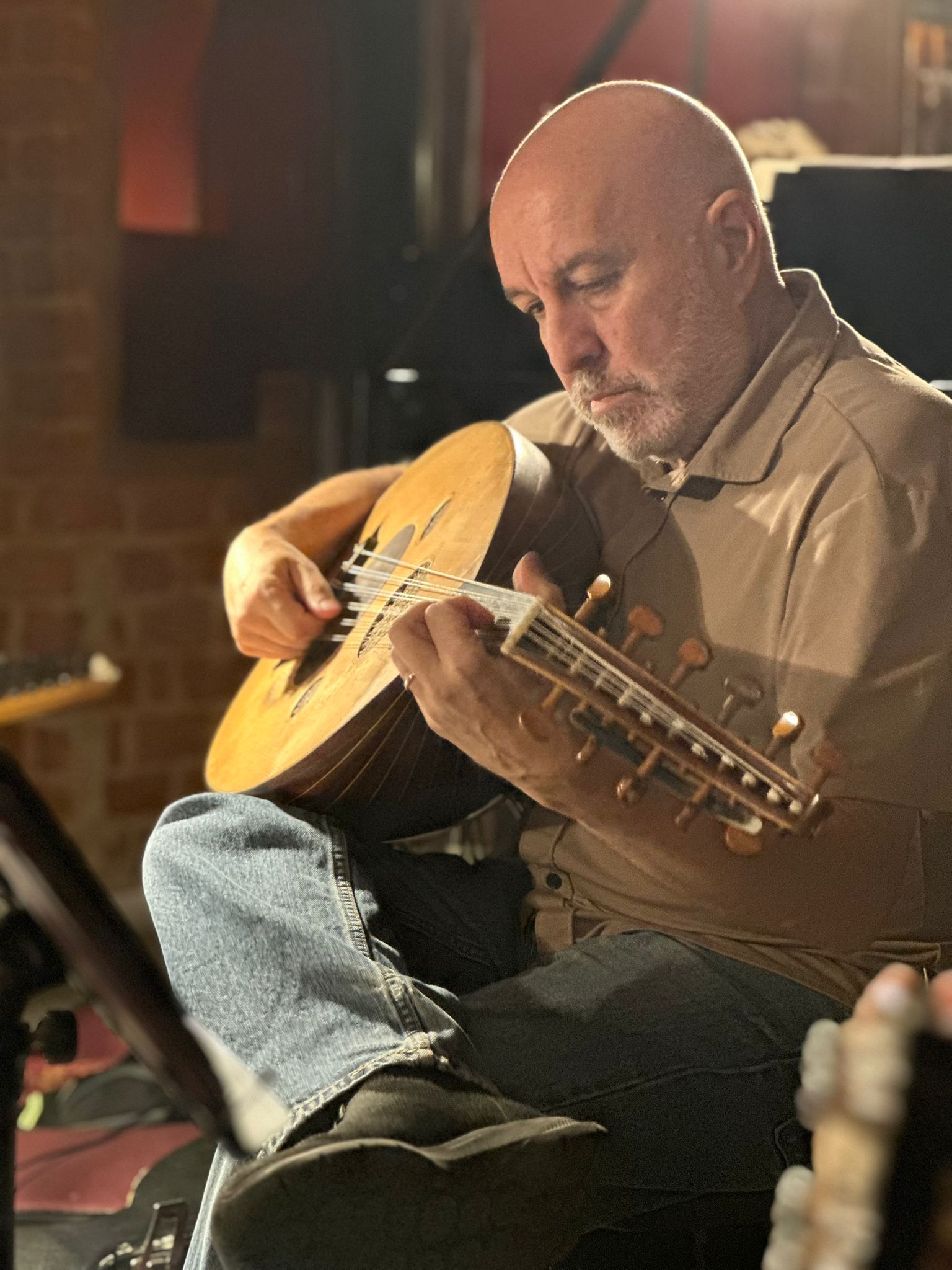

I’ve listened to him since childhood, since Night Ark. Later, his collaborations in Greece with Eleftheria Arvanitaki and in Turkey with Sezen Aksu made him popular. Ara’s approach is unique; when he touches the oud, it draws you into the music’s essence. It’s like pausing time. That perspective on music has become my compass, too.

How did this collaboration take shape, and what can the audience expect from the concert?

It all started with Yaşar Tolga Cora from Boğaziçi University, who had the idea of bringing Istos and Ara Dinkjian together. With Onur Günay and Ülker Uncu supporting the idea and giving glowing references, suddenly we found ourselves deep in preparations. When I first met Ara, I explained that we weren’t a traditional choir —he could think of us as people happily playing and singing around a table. My vision was to bridge two generations: combining his father Onnik Dinkjian’s traditional Diyarbakır Armenian pieces with Ara’s contemporary compositions. He liked the concept. Until he arrived for the first rehearsal months later, he hadn’t heard us play —but when he did, he was pleased with what he saw.

Last question. Where in Istanbul do you feel most alive?

Beyoğlu. Period.

I do not ask why…

Chaos, history, complexity… You can be alone in the crowd. No matter how identities shift in time, the spirit is still there. Its heartbeat is different. We must embrace that.

If Istanbul were a table, what would you place on it?

A simit. A glass of tea. The clink of a spoon. The ding of a tram. A cat’s paw brushing gently against your leg. The cry of a seagull. That’s Istanbul in a glance.

To follow Fotini Kokkala and the Istos Choir: Instagram / @fotinikokkala and @istoskorosu YouTube / @NikoTeini and @istoskorosu815

English

English